“The Vice Presidency turned out to be just what Jefferson had predicted: ‘philosophic evenings in winter’ and summers at his beloved Monticello.”

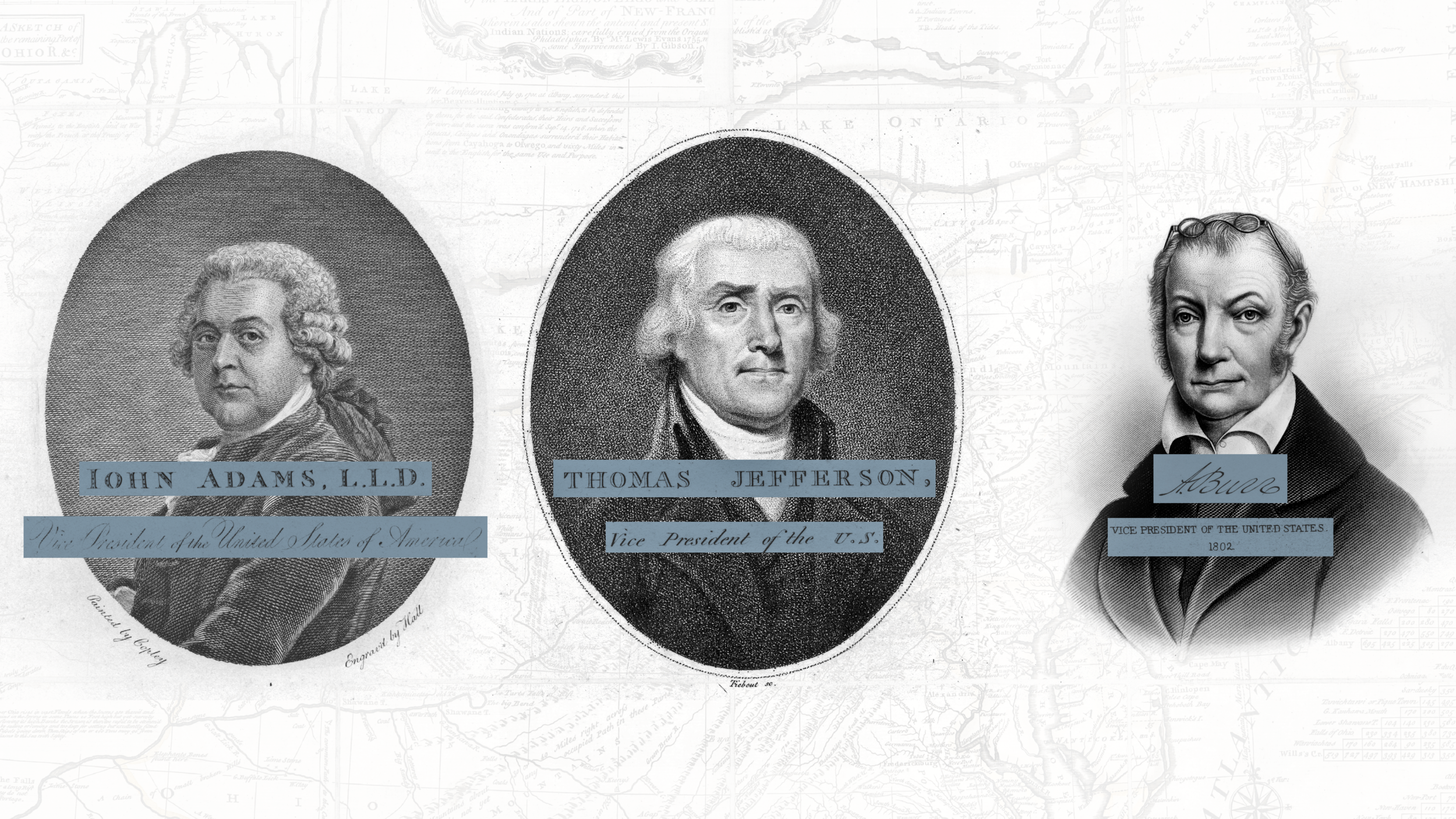

This week on the Thomas Jefferson Hour, we return to "Jefferson 101", our biographical series. Reluctantly, Jefferson came out of retirement to serve as vice president for four years under his old friend John Adams. They were of different political persuasions and they, in a sense, became the heads of different political parties. Adams & Jefferson were friends when Jefferson's vice presidency began but there was a long period afterwards when they couldn't really abide each other; in the end, in 1812, their friendship was restored and it became one of the great reconciliations of American history. During his vice presidency, Jefferson contributed a rule book to the Senate: A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States.

Jefferson meant it: He preferred the happiness of Monticello to the burdens of power — but he loved this country more than he loved his own happiness.

This is Jefferson 118.

Clay will be performing as Thomas Jefferson at the Ferguson Center for the Arts in Newport News, VA on April 19th, 2017. Find more info and buy tickets here.

Becky Cawley • (208) 791-8721 • odytours.net

Further Reading:

- Isaac Granger Jefferson

- Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Rush, January 22, 1797

- Thomas Jefferson's A Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States

Show Notes

From Jefferson's Manual of Parliamentary Practice for the Use of the Senate of the United States:

SEC. I—IMPORTANCE OF ADHERING TO RULES

Mr. Onslow, the ablest among the Speakers of the House of Commons, used to say, ‘‘It was a maxim he had often heard when he was a young man, from old and experienced Members, that nothing tended more to throw power into the hands of administration, and those who acted with the majority of the House of Commons, than a neglect of, or departure from, the rules of proceeding; that these forms, as instituted by our ancestors, operated as a check and control on the actions of the majority, and that they were, in many instances, a shelter and protection to the minority, against the attempts of power.’’ So far the maxim is certainly true, and is founded in good sense, that as it is always in the power of the majority, by their numbers, to stop any improper measures proposed on the part of their opponents, the only weapons by which the minority can defend themselves against similar attempts from those in power are the forms and rules of proceeding which have been adopted as they were found necessary, from time to time, and are become the law of the House, by a strict adherence to which the weaker party can only be protected from those irregularities and abuses which these forms were intended to check, and which the wantonness of power is but too often apt to suggest to large and successful majorities, 2 Hats., 171, 172.

Thomas Jefferson to Dr. Benjamin Rush, January 22, 1797:

I thank you too for your congratulations on the public call on me to undertake the 2d office in the U S, but still more for the justice you do me in viewing as I do the escape from the first. I have no wish to meddle again in public affairs, being happier at home than I can be anywhere else. Still less do I wish to engage in an office where it would be impossible to satisfy either friends or foes, and least of all at a moment when the storm is about to burst, which has been conjuring up for four years past. If I am to act however, a more tranquil & unoffending station could not have been found for me, nor one so analogous to the dispositions of my mind. It will give me philosophical evenings in the winter, & rural days in summer.

A Cul-de-Sac and a Bucket of Piss

From Clay:

Disenchantment with the Vice Presidency began early. The nation’s very first Vice President John Adams called the office "the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived."

"I am Vice President,” Adams lamented, “In this I am nothing, but I may be everything."

A hundred years later, Theodore Roosevelt called the Vice Presidency a “cul de sac,” and suggested that the office ought to be abolished.

The 32nd Vice President John Nance Garner, who served under FDR, is often quoted as saying the vice presidency is “not worth a bucket of warm spit,” when in fact the term he used was “a bucket of warm piss.” Nance, a Texan, said accepting the Vice Presidency was “the worst damn fool mistake I ever made.”

Read Clay's Jefferson Watch essay, "A Cul-de-Sac and a Bucket of Piss".

What Would Jefferson Do?

“The person who received the largest number of electoral votes would be president and the person who received the second largest number of electoral votes would be vice president.”

Tune in to your local public radio or join the 1776 Club to hear this episode of What Would Thomas Jefferson Do?

Jefferson 101 is a series of biographical shows about the life of Thomas Jefferson that ran from 2016 to 2017.

Jefferson was a pragmatic utopian, and a utopian pragmatist.

I’m a devoted American patriot. I love this country, but I want it to be more like the country I love than the disillusioned, vulgar, and divisive place it has become.

"Two seraphs await me long shrouded in death; I will bear them your love on my last parting breath."

— Thomas Jefferson, July 1826

We conclude our Jefferson 101 biographical series by discussing his final days at Monticello, his legacy, and the deaths of both Jefferson and John Adams on July 4th, 1826 — the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.