In mid-August of 2014, I received a single Jefferson pea in a small brown envelope, along with a copy of Robinson Crusoe. I was also issued a challenge: to use the book as inspiration and the pea as seed stock to build a Jeffersonian pea empire.

The Swinish Multitude

And So the Great Adventure Begins

Roosevelt and Pinnacles National Park

You Must Go Home Again

Above the Tide Pools

Travels with Karli, and Fred, and Roger

Praise God for Vittory

The Steinbeck Journal

I Love What I Get to Do

Godspeed Sheila Schafer

Sheila (shy-leh) Schafer died quietly in her sleep on Tuesday March 15, 2016, in Bismarck, North Dakota. She was 90 years old.

She was the most life-affirming person I ever met in the whole course of my life. I met her ten years ago when I moved back to North Dakota. We became friends, then good friends, then extremely close friends. But I was merely one of hundreds of Sheila's friends.

“Sheila Schafer was always the youngest person in every room.”

She was the wife of North Dakota's first great millionaire, Harold Schafer, the founder of the Gold Seal Company (Mr. Bubble, Snowy Bleach, Glass Wax), and the philanthropist and visionary who turned the sleepy little town of Medora into North Dakota's premier tourist destination. She was the mother of eight children, five of Harold's, three of her own. One of those children, Ed Schafer, was the governor of North Dakota between 1992-2000 and later George W. Bush's Secretary of Agriculture.

She was the center of attention no matter where she went or what she did, and she delighted virtually everyone she ever met. She was a master raconteur, a natural comic, and her heart was as large as the American West. She was on a first name basis with Presidents, governors, ambassadors, rock stars, and thousands of people whose names she always remembered but you and I have never met.

The famous Medora Musical, which was largely her creation, entertains more than 100,000 people per summer in a town of about 108 permanent citizens. To see the Musical with Sheila was to watch two shows: the Musical, and Sheila watching the Musical. Sheila's Musical was almost a contact sport: she whooped, hollered, cheered, teared up, clutched her heart during fireworks, shouted "Hi, Band!" when the musicians first took the stage, and then stayed afterwards to give words of encouragement to the cast and crew. Countless times sitting next to her in the fifth or sixth row, I have watched people come up to kneel before her--to say, "You probably don't remember me, but when my father was ill, you and Harold helped us out. . . . You may not remember me, but when I was working in Medora one summer, you brought me a ice cream bar on the hottest day of July, and said, good work, keep it up, and enjoy Medora!"

She pleased multitudes without ever seeming insincere. She laughed easily, often, and hard, and was able to laugh at herself without the slightest pride or reluctance.

The longer I knew her the more amazed I was: to be counted among her hundreds of friends; to witness her amazing anonymous acts of kindness and thoughtfulness; to observe her high intelligence and savvy analysis of situations near and far away; and to see what willful optimism can do to turn virtually any situation into joy and possibility.

Three times since I met her I have been told that she would die in the next 48 hours, and each time when Death came for her she sent him packing: not yet, not now. The last of these moments came more than five years ago! I had come to think of her as immortal, for her mighty and youthful spirit kept her alive long after her body had broken down. Finally, not even Sheila Schafer could prevail against the fragility of old age. She died with dignity.

I will miss her more than I could ever say. She made the difference in my life these last ten years. My live would have been so much less without her. And though her legacy--adventures, stories, style, laughter, generosity of spirit--will live on in all who knew her, the simple fact is that my life will be so much less without her.

Recording Complete of the Audio Version of Becoming Jefferson’s People

A number of years ago I wrote a short book called Becoming Jefferson’s People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century. It is my attempt to describe what it is to be a Jeffersonian, and how a more Jeffersonian America would re-invigorate our national politics and culture.

A few weeks ago I recorded an audio edition of the book at Makoché Recording Studios in Bismarck, North Dakota. We are doing the last of the post-production of the book now. It will soon be available on audible.com.

By “Jeffersonian,” I mean something like the following combination. A citizenry that reads books for pleasure and enlightenment; a more emphatic and committed public education system; a belief that “reason is our only oracle,” and that science should be permitted to shape (even dictate) public policy; a deep commitment to civility, generosity of spirit, epistolary correspondence, and harmony; growing some of one’s own food, if only a tomato and a patch of peas; a preference for temperance (wine) over intoxication; a deep and abiding curiosity; a commitment to international peace and non-violence; and an insistence that government should only do such things as it alone can do.

Read more here.

The Signature Books of My Life

The most frequently asked question by people who come into my house is, “Have you read all these books?” And even though it is a natural and inevitable question, it is a question that so fundamentally misunderstands the life of the mind, the life of the reader, that I have a hard time not responding in sarcasm.

Review my list of primary texts here.

Thomas Jefferson in Norfolk, VA, Next Week!

March 22 & 24

I cannot wait to return to Norfolk, Virginia, where I have performed Jefferson and other historical characters for the past decade or more. I love our east-coast flagship station WHRV/WHRO, and the people there who do so much for public radio and the humanities. I have close friends in the lower Chesapeake. The Roper Theater has been the venue of some of my favorite public performances. I hope you can attend one of two performances coming up in March 22 & 24.

For details, visit WHRO.

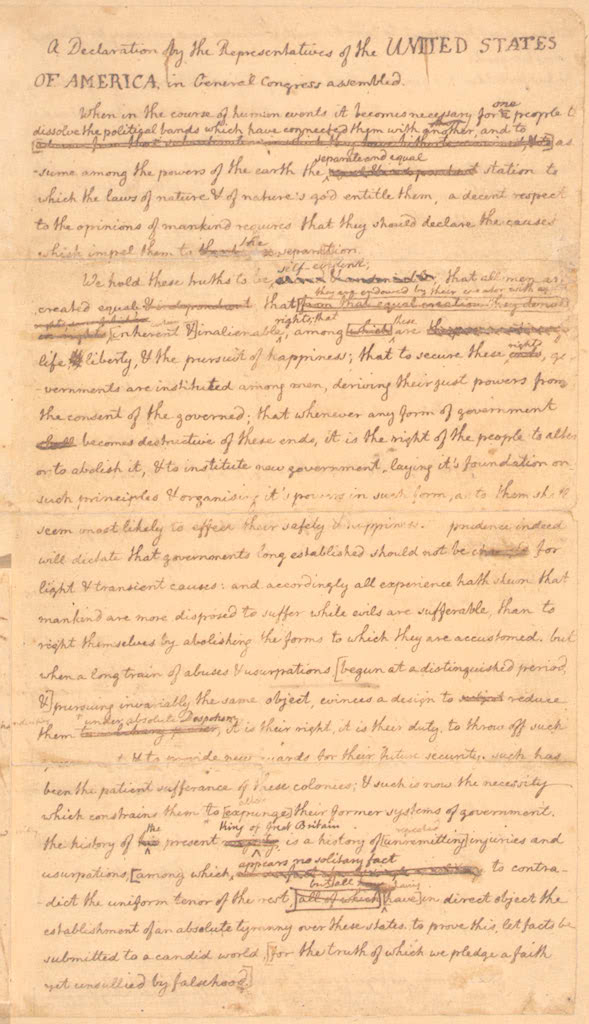

Nancy Reagan, the GOP, and Jefferson's draft of the Declaration of Independence

Jefferson 107: the Original Draft of the Declaration of Independence

“We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable...”

This week on The Thomas Jefferson Hour, the semi-permanent guest host David Swenson and I discuss Jefferson’s original text of the Declaration of Independence. It's part of our 20-episode out of character biography of Thomas Jefferson. Stay tuned as we work our way through the life of one of America's greatest individuals.

On the Death of Nancy Reagan

Whatever one thinks of the politics of the Reagans, they had class. They brought decorum to all that they did. They took themselves seriously because they took America seriously. President Reagan understood Jefferson's principle that to be president of the United States you have to sing the Song of America. How appalled Reagan would be by the antics of the 2016 Republican candidates for president.

To read my short essay on the legacy of Nancy Reagan, click here.

The Republican Establishment - Beware What You Ask For

I’ve been watching with great amusement the Republican establishment’s attempts to stop Donald Trump from winning the nomination. Something very similar happened in 1912, when former President Theodore challenged the incumbent, his former friend William Howard Taft for the Republican nomination. it is never a good idea to thwart the will of the people. Are you listening (or reading your history) Republican establishment?

Read more here.

Latest News on the New Theodore Roosevelt National Presidential Library in North Dakota

You may know that we are building a magnificent national Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in Dickinson, North Dakota. Our design committee met out on the Oregon coast last weekend to discuss the stories we want to tell at the TR National Presidential Library and Museum. The weekend ended with a propitious sign tossed up by the Pacific Ocean. Read more here.

For more information on this exciting project, visit the Theodore Roosevelt Center.

Buffalo Bill Cody and the Invention of the West

Sunday, March 13, 2016 at 3 pm CST

Conversations at Bismarck State College occur five times per academic year, led by BSC President Larry Skogen and humanities scholar Clay S. Jenkinson.

This Sunday, March 13, President Skogen and I will explore the life and achievement of Buffalo Bill Cody, his relations with American Indians, and the way in which he depicted Indians in his shows both in the United States and Europe. We will base our conversations on Cody's autobiography (1920), and Louis S. Warren's Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody and the Wild West Show.

Our discussion will try to make sense of what has been called the "inauthentic authenticity" of Buffalo Bill's life and career. What was it about America in the 1880s and 90s that packed his arenas with audiences hungry to make sense of our frontier history? To what extent did Cody "represent" frontier history and to what extent did he "invent" it?

Later this spring (BSCtalk.org) we will explore North Dakota's Dust Bowl Years, and George Armstrong Custer's 1874 reconnaissance of the Black Hills.

You can watch live online. For information and the live stream link at 3 pm CST on Sunday, click here.

Lewis & Clark Summer Tour in Montana

July 17-26, 2016

Every summer I lead 20-30 individuals through the White Cliffs section of the Missouri River in Montana, and then up on the Lolo Trail in Idaho west of Missoula. We follow precisely in the footsteps of Lewis and Clark. It's the highlight of my travel year. If you listen to the Thomas Jefferson Hour, you have heard of the infamous "Wendover Death March." For many, this is a life-changing adventure.

Jefferson would have loved to go on this journey, if he could have brought a keel-boat of wine, another of books, writing instruments, scientific devices--and Madison to do the heavy lifting!. Space is limited, reserve your spot here.

Announcing Completion of Audio Recording of Becoming Jefferson's People

“Reason and free inquiry are the only effectual agents against error. Give a loose to them, they will support the true religion by bringing every false one to their tribunal, to the test of their investigation.”

Over the past couple of days I have recording an audio version of my book Becoming Jefferson's People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century.

I love voice work and want to do much more of it. I plan to record the audio of my book of essays about North Dakota; and my study of the life and character of Meriwether Lewis. I hope also (in the next year) to record books that I did not myself write, but that are among my favorite books: Thoreau's Walden; Cather's My Antonia; The Iliad; Hamlet; etc.

Strange to say, I have not actually read Becoming Jefferson's People for ten years. My life is like a freight train—pushing me along to the next project, the next book, the next journey. At this remove, I even have a hard time remembering just when I decided to write Becoming Jefferson's People, and the exact process of writing it.

Here's what I felt and discovered in the last couple of days in the Makoché Recording Studios in Bismarck, North Dakota.

1. I believe this is an important book and I wish all of our political candidates, legislators, and political pundits would read it.

If you have any way of getting the book into the hands of people who are "in the arena" of our national political life, please help. I'm serious. I believe that Jefferson's vision of an American republic is the right one; that it is not too late to redeem and reclaim our culture; and that this voice needs to be part of the national conversation.

2. I'm really proud that I wrote Becoming Jefferson's People.

It's spot on, I believe, and it confirmed my belief that it's Jefferson's America I want to live in, not Hamilton's, not FDR's, not G.W. Bush's, not Obama's. I think it is essential that all of us dream of the world we want to live in, and then work hard to bring that world into being. I want to live in Jefferson's world, updated to jettison that in his perspective that no longer works (slavery, patriarchy), but clarifying and re-invigorating that which is essential to an enlightened nation.

3. I was inspired in reading the book to live a more jeffersonian life.

The book is a kind of aspirational vision of the enlightened life. But it is also a mirror we can hold up to our own lives, to test them against the ideals of rationality, civility, science, and generous skepticism. Heck, if I was inspired reading my own book (!), I think others will be inspired too.

Here are a couple of passages that I really like:

"Suspicious of positive government, Jefferson believed that education is the panacea, that almost all social ills will disappear in a better informed and better educated nation."—Does any not agree with this?

"Jefferson loved books as books, and regarded them as sensuous objects, and even works of art. He made sure that his beloved books were elegantly and sumptuously bound, shelves in aesthetic good taste, and classified intelligently."

"In spite of all that the evangelicals pretend, the Constitution of the United States is entirely silent on questions of religion. God is never mentioned in the Constitution, not even as the 'Creator' or 'Nature's God' (both from the Declaration of Independence)."

"Jefferson believed that we exist to be happy, not to struggle through life or perform duties or deny ourselves pleasures. There is nothing dour or Calvinist in the Jeffersonian temperament. No day should unfold without the pleasures of food, wine, nature, flowers, exercise, correspondence, family, friendships, books, art, music, and contemplation. And love."

If you want to read this book you can purchase it at Amazon.com. The audio version of the book will be available in a couple of weeks. We're going to use it as a "premium" for $75 subscribers to the Thomas Jefferson Hour, and it will be available probably at Audible.com. Stay tuned!

Further Reading:

- Becoming Jefferson's People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century by Clay S. Jenkinson (Audiobook) (Amazon)

- The Character of Meriwether Lewis: Explorer in the Wilderness by Clay S. Jenkinson

- For the Love of North Dakota and Other Essays: Sundays with Clay in the Bismarck Tribune by Clay S. Jenkinson

- Message on the Wind: A Spiritual Odyssey on the Northern Plains by Clay S. Jenkinson

- Read Jefferson’s entire passage from Notes on Virginia about religious liberty.

More from the Thomas Jefferson Hour

Recording the Audio Version of Becoming Jefferson's People

Thomas Jefferson and the Supreme Court

“[John Marshall’s] twistifications in the case of Marbury, in that of Burr, & the late Yazoo case, shew how dexterously he can reconcile law to his personal biasses”

Jefferson had a strange and now discredited relationship with the Supreme Court. Because he was an ardent republican--that is, one who believed that the people are sovereign and that they should govern themselves through majority rule--he was severely critical of the idea of "Judicial Review." The concept of judicial review (judicial veto) is nowhere articulated in the Constitution of the United States. It was foisted upon the Constitution by Jefferson's distant cousin and bete noir John Marshall, in the famous case Marbury v. Madison in 1803.

Jefferson's view was that if the Founding Fathers had wanted to give the Supreme Court the power of judicial review, they would have written that power into the Constitution in 1787. He regarded Marshall's brilliant decision in Marbury v. Madison as a kind of silent junta that overthrew the clear intentions of the Constitution.

Jefferson believed so strongly in the sovereignty of the people that he nearly subscribed to Rousseau's principal that 'the people are always right even when they are wrong.' Jefferson advocated what might be called a "tripartite" theory of the Constitution: that each of the three branches of the national government should interpret the constitution, and that no single branch should be the final arbiter. He would have preferred the courts to be senior advisers who might suggest that Congress had overstepped its bounds or violated some principle of the Bill of Rights or the Constitution, but that these pronouncements would be advisory rather than determinative.

Jefferson also believed that the states, including individual states, should have the right to weigh in on constitutional questions, because the Tenth Amendment made them sovereign in all affairs not truly national or international, and that they would need to guard their limited sovereignty against national government encroachments. This was the basis of his Kentucky Resolutions in 1798.

Jefferson's system may have been "republican," but it was not workable, and it has long since been relegated to a jurisprudential Siberia.

The Supreme Court is thus infinitely more powerful in our time than it was in his. Today, nine unelected and essentially unimpeachable men and women can affect the lives (and rights) of a third of a billion people. Jefferson would find this absolutely appalling both in constitutional (and republican) theory and practice. In Jefferson's terms, why should the nine members of the Supreme Court be able to set policy for 330 million other people about such issues as abortion, religious expression, gay marriage, stem cell research, eminent domain, etc.? These questions are so important--in Jefferson's mind--that they must be decided by The People--not a tiny handful of men and women who clearly have good days and bad days, prejudices and biases, politics, and hidden sympathies. To put so much power into the hands of so few is inherently un-republican and un-Jeffersonian.

Keep in mind that when I use the term "republican" (see above), I mean "of classical republican theory" and not the modern Republican Party.

Jefferson named three men to the Supreme Court. William Johnson of South Carolina served from 1804-1834. Henry Brockholst Livingston served from 1806-1823. And Thomas Todd served from 1807-1826. Todd has been called one of the two or three most ineffectual justices in American history. Livingston generally sided with Chief Justice Marshall. And though Johnson was a serious Jeffersonian, even he disappointed the state's rights republican president during TJ's time in the presidency--and after.

Congress approved Jefferson's appointments with grace. Members of the Senate recognized rightly that the President had a duty to fill vacant seats and a right to surround himself with people of his own political persuasion. Elections matter. And Congress cannot nominate Supreme Court justices. Congress can only approve or refuse to approve.

Further Reading:

- Founders Online: Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, 25 May 1810

- What Kind of Nation: Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and the Epic Struggle to Create a United States by James F. Simon

- The Constitutional Thought of Thomas Jefferson by David N. Mayer

- Jefferson's Vendetta: The Pursuit of Aaron Burr and the Judiciary by Joseph Wheelan

U.S. Supreme Court building, Washington, D.C., c. 1943. Public domain from the Library of Congress via Flickr.

John Marshall: The Greatest Lame Duck Appointment of All Time

I have never felt any enmity towards you Sir for being elected president of the United States. but the instruments made use of, and the means which were practised to effect a change, have my utter abhorrence and detestation, for they were the blackest calumny, and foulest falsehoods.

Abigail Adams to Thomas Jefferson

John Adams and the Federalists were appalled when Thomas Jefferson was elected to the Presidency in the autumn of 1800. They regarded Jefferson as a dangerous radical who was bent on destroying Federalist financial system (the national debt, the National Bank of the United States), and who might sweep all Federalist bureaucrats out of office.

Adams and his Federalist partisans in Congress decided to forestall what Jefferson was calling "the second American revolution," by packing the court system with men who were known Jefferson detractors.

In haste and even some desperation, Adams nominated Virginia's John Marshall to be Chief Justice of the United States. This happened after the presidential election of 1800, and just a few weeks before Jefferson was inaugurated as the Third President of the United States. Now THAT'S a lame duck appointment!

Marshall was confirmed by the Federalist (lame duck) Senate on January 27, 1801, several months after Jefferson won the election.

Jefferson cried foul. In a letter to Abigail Adams on July 1, 1804, Jefferson wrote, "I can say with truth that one act of Mr. Adams's life, and one only, ever gave me a moment's personal displeasure. I did consider his last appointments to office as personally unkind. They were from among my most ardent political enemies, from whom no faithful cooperation could ever be expected, and laid me under the embarrassment of acting thro' men whose views were to defeat mine; or to encounter the odium of putting others in their places."

Because he was an unusually civil man, and because it was the early Nineteenth Century (the age of Jane Austen), Jefferson expressed his anger in hurt in this somewhat periphrastic way. Notice that he did not mention his distant cousin John Marshall by name.

But he could not let his anger go. "It seemed but common justice," he continued, "to leave a successor free to act by instruments of his own choice."

Think about this for a moment. John Adams had been repudiated by the American people. He was not in the last months of his term, but in the last weeks, AFTER he had been defeated by Jefferson in the election of 1800. Nevertheless, Adams made a range of "midnight appointments," a few of them in the last days and even last hours of his troubled one-term presidency.

The principal midnight appointment, John Marshall, turned out to be one of the greatest, if not the greatest, justice of the Supreme Court in American history. He really was an avowed enemy to Thomas Jefferson, and he really did refuse to provide "faithful cooperation" during Jefferson's eight years as President.

Who was right? Both Adams and Jefferson had legitimate grievances against the other, and there is no question that Adams appointed Marshall to the court to stymie and embarrass Jefferson. In other words, Adams was not appointing Marshall out of any pure sense that he was the best man in America for so important a post. He wanted to damage his former friend Jefferson, who had undermined his administration and who had now displaced him as President. That Marshall turned out to be an outstanding justice was no part of Adams's strategy.

Abigail Adams replied to Jefferson's letter on July 1, 1804. She not only put Jefferson firmly--even rudely--in his place, but gave him a little course in U.S. Constitution 101:

"The constitution empowers the president," she wrote, "to fill up offices as they become vacant. It was in the exercise of this power that appointments were made, and Characters selected whom Mr. Adams considered, as men faithful to the constitution and where he personally knew them, such as were capable of fulfilling their duty to their country."

Then Mrs. Adams played the ultimate American trump card. "This was done by president Washington equally, in the last days of his administration, so that not an office remained vacant for his successor [John Adams] to fill upon his coming into office."

Abigail Adams was right! The President of the United States is the head of the American government from the moment he is inaugurated (then March, now late January) until the moment his successor is nominated, and that person is not only empowered by the Constitution to perform all presidential functions during that swatch of time, but required to perform those duties.

Adams had every right to appoint John Marshall to the Supreme Court. And President Obama has every right--and a constitutional duty--to appoint a successor to the seat filled for thirty years by Antonin Scalia.

The Republicans (and Jefferson) can squawk all they want, but the clear meaning of the U.S. Constitution favors a sitting President. The Senate can refuse to affirm the President's appointee, but THAT would be a greater offense to the U.S. Constitution than the President's timely appointment.

And who knows? Maybe the next great justice of the Supreme Court, a Twenty-First Century John Marshall, is in the wings.

Further Reading:

- UVA Press: To Thomas Jefferson from Abigail Smith Adams, 1 July 1804

- The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams edited by Lester J. Cappon

- What Kind of Nation: Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and the Epic Struggle to Create a United States by James F. Simon

- America's Constitution: A Biography by Akhil Reed Amar

American Political Campaigns Have Always Been Nasty

The other [party] consists of the ill-tempered & rude men in society who have taken up a passion for politics. From both of these classes of disputants, my dear Jefferson, keep aloof, as you would from the infected subjects of yellow fever or pestilence. Consider yourself, when with them, as among the patients of Bedlam needing medical more than moral counsel. . . . Get by them therefore as you would by an angry bull: it is not for a man of sense to dispute the road with such an animal. You will be more exposed than others to have these animals shaking their horns at you, because of the relation in which you stand with me.

Jefferson to Thomas Jefferson Randolph

November 24, 1808

Speaking at Springfield, Illinois, a day or two ago, President Barack Obama reminded his audience that vicious partisanship is not unique to our own time. He noted some of the terrible things said of Abraham Lincoln in his lifetime, and Andrew Jackson, but he reserved his longest citation for Thomas Jefferson.

In the ugly election of 1800, a Federalist newspaper warned that if the Jacobin fanatic Jefferson were elected, the American people could expect that "murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood and the nation black with crimes."

Actually, Jefferson turned out to be a mild-mannered President. The worst that he did, from the Federalists' point of view, was turn out of office a few score of diehard Federalists who refused to make peace with his administration. And he convinced a friendly Congress to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801 (thus reducing the number of judgeships), and to impeach two Federalist jurists (John Pickering of New Hampshire and US Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase).

Jefferson's enemies were sure he would bring about a Reign of Terror in the United States--or at least they pretended to. They called him an atheist (which he was not), a Jacobin (untrue), an enemy to Christianity (not really true, but there is a small grain of distorted truth in the charge), a despoiler of widows' estates (absurd), and the father of a slave's children (hem!).

The same anti-Jeffersonian newspaper asked, "Are you prepared to see your dwellings in flames, female chastity violated, children writhing on a pike?"

Jefferson refused to respond to any of this nonsense. He regarded his religious views as strictly private, and no business of the American people; and he felt that if he responded to one attack it would be like Hercules fighting Hydra--cut off one head and two more spring up as if by magic.

In the end, Jefferson won the election (in a narrow, contested election). He presided over eight years of peace and prosperity, reduced the national debt, doubled the size of the American republic for three cents per acre, sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the shores of the Pacific, fought an undeclared naval and marine war against the Islamic pirates of north Africa, and reduced the size of the national government.

No children writhing on the pike!!!

I do believe many well-meaning Americans feared that Jefferson was too radical to be trusted as the leader of the United States. Many well-meaning Americans worried that a Deist (semi-atheist) President would erode the social fabric of the nation. Some were sorry to see a slaveholder whose election was made possible by the Three Fifths Clause preside over a nation dedicated to liberty.

Jefferson surprised many and "disappointed" his hotheaded critics by presiding over the country with modesty and mostly-mild policies. He served exquisite foods and wines at the White House.

And he gave as good as he took. He encouraged the disreputable pamphleteer James Callender to write nasty things about John Adams.

So much for civility.

President Obama spoke of these things with a sense of bemusement that must be an example of what Jefferson called "artificial good humor."

Further Reading:

- Founders Online: From Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Jefferson Randolph, 24 November 1808

- Jefferson's Second Revolution: The Election Crisis of 1800 and the Triumph of Republicanism by Susan Dunn

- America Afire: Jefferson, Adams, and the Revolutionary Election of 1800 by Bernard Weisberger

- A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign by Edward J. Larson

So Just How Political Was Thomas Jefferson, Anyway?

Thomas Jefferson thought of himself as a farmer, amateur scientist, and man of letters who preferred not to get drawn into the "disagreeable business of politics." He believed he was above politics. He convinced himself that he was a commonwealth man, who wanted America to be the most rational, civil, scientific, and harmonious society in human history. He always believed (with some justification) that his views of America represented the vast majority of the farmer-citizens of the new republic.

Help Me Find the "New Jeffersonians"

"I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Painting and Poetry Mathematicks and Philosophy."

John Adams to Abigail Adams

May 12, 1780

One of my favorite themes is the quest to be Jeffersonian. By that I mean something like, a: committed to rationality; b: rooted in the land in some dynamic way; c: devoted to books; d: optimistic about the human project; e: suspicious of government as a routine answer to human problems; f: self-sufficient; g: civil; h: respectful of science, knowledge, evidence, learning, scholarship, and the use of reason as the chief tool of human progress.

I know people who prefer pro-football to reading, and jet skis to gardening. Fair enough. The great paradox of freedom is that people are free to pursue happiness in ways we don't necessarily admire. (And I always remember: they regard me/us as the inexplicable outlier in the quest for happiness. As long as you remember that, you will do well in America.)

But the people who admire the life and achievement of Thomas Jefferson, the people who listen to the Thomas Jefferson Hour, are usually either Jeffersonians or people who aspire to the Jeffersonian.

I'm often asked to name Jeffersonians in American life. Names like Wendell Berry, Wes Jackson, the late Carl Sagan, and others usually come to mind. But this is not, at least with respect to public figures, a very Jeffersonian time.

But my interest at the moment is young Jeffersonians, new Jeffersonians. People who admire gadgets and gimcracks as Jefferson did. People doing interesting things in wine. People who are making bold innovations in the culture of the book and the library. Young agrarians who are engaged in the farm to table movement. Architects, paleontologists, archaeologists. People who are fascinated by modern networking and cultural dissemination, including the dissemination of revolutionary ideas. Young political leaders who have adopted Jeffersonian principles. Explorers like Jefferson's protege Meriwether Lewis. People interested in space. And so on.

I'm not interested in narrow professionals. What made Jefferson Jefferson is that he was a gifted amateur, who took all knowledge to be his province. He was equally adept at designing a skylight as he was at writing a state paper. He was as precise in organizing his garden as he was in organizing the Library of Congress. He had (one definition of genius) "an infinite capacity for taking pains."

If you know of such young people, please let me know about them. I want to meet them and interview them on the Thomas Jefferson Hour, even if they do not regard themselves as Jeffersonians, or have no particular Jefferson interest.

It is abundantly clear to me that the Baby Boomers have had their chance to create the Age of Aquarius, and it turns out to look pretty much like a much more materialistic version of the world they inherited, and certainly more narcissistic. I'm interested in finding young Jeffersonians, and asking them to help us see the world through a clearer lens.

Further Reading:

- Library of Congress: Thomas Jefferson to James Monroe, March 2, 1796

- Becoming Jefferson's People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century by Clay S. Jenkinson

Self-Soothing by Way of Erasing the Complexity of Human History

“Every human being must be viewed according to what it is good for. For not one of us, no, not one, is perfect. And were we to love none who had imperfection, this world would be a desert for our love.”

My beloved mentor in the humanities, Everett C. Albers, taught me the most important of all lessons: "Judgement is easy, understanding is hard."

You probably have been following the recent spasm of righteousness on some of our college campuses. Some students wish to erase all traces of Woodrow Wilson at Princeton University, because he was a racist who undid what little integration his predecessors had managed in the federal government; because he was a sexist, who actively worked against women's suffrage. Some students wish to have statues of Thomas Jefferson removed from the campus of the University of Missouri, because he was a racist, a slaveholder, and a sexual predator (if you read the Sally Hemings story in the darkest possible way). Some students at Oxford University wish to erase all traces of Cecil Rhodes, after whom Rhodesia was named, because he was a racist and an imperialist.

And so on.

It is true, by our standards as exemplars of perfect enlightenment, these men were all racists and indeed apartheidists. I have a close connection with two of them: Jefferson, whom I have been studying for thirty years, and Rhodes, whose scholarship I freely accepted back in 1976, and under whose financial legacy I studied for four wonderful years at Oxford University. I know the life and achievement of Woodrow Wilson less well, but I have read a handful of books about him over the years.

I regard this growing trend of purification rituals as wrong-headed and misguided for a number of reasons. I'll list them as briefly as possible.

1. What will they say of us? Sometimes I try to anticipate what the righteous ones of the future will say about us? I met a petrochemical engineer a number of years ago. We talked for several hours about oil as a miracle carbon. I asked her what the epitaph of Western Civilization would be. She said. "They burnedoil." This morning I'm wearing shoes, socks, boxers, trousers, and a shirt, not one item of which was made in the United States. If I could trade each item of clothing back to the factory of its manufacture, I doubt that I would sleep well tonight. I'm with Jesus, John 8:7, "let him who is without sin cast the first stone."

2. The whole man theory. As Jefferson wisely explained to his daughter Martha (see above), every human being is a mixed bag: enlightenment and blind prejudice, generosity and narcissism, benevolence and malevolence, good day and bad day, clarity and blind spot, outstanding in some ways, deplorable in others. Think of Lance Armstrong, Bill Cosby, Benito Mussolini, Bill Clinton, Mother Teresa, Margaret Thatcher, for example. In selecting our culture heroes, we have to assess the whole life and the entire achievement.

Jefferson was a racist and a slaveholder. These factors should weigh heavily in any rational assessment of his life and character. But we must also place in the balance his magnificent labors as a benefactor of humankind: decimal coinage, the rectangular survey grid system, separation of church and state, the University of Virginia, the organizational principle of the Library of Congress, the Louisiana Purchase, the design for the Capitol at Richmond, VA, fundamental work in paleontology, the Declaration of Independence, and the software of the American dream.

For all of his faults--and they do not begin and end with slavery--is Jefferson, in the final analysis, a benefactor or a degrader of humankind? On balance, how shall we evaluate him? Looking at his whole 83 years, his mass of writings, his range of practical achievements, his acts of greatness and his weakest moments, how shall we finally assess him?

3. Hamlet's view. When the aging courtier Polonius tells Hamlet he will treat the visiting theater group "according to their desert," Hamlet responds passionately: "God's bodykins, man, much better! Use every man after his desert, and who should 'scape whipping." -- Precisely. Where does this erasure of the past, more reminiscent of Stalin's USSR and Orwell's 1984 than of an enlightened democracy, end exactly? George Washington was a slaveholder. Lincoln had race views that would get him razed from Mount Rushmore by the narrowly righteous. Elizabeth Cady Stanton said remarkably ugly things about African-Americans when black men got the vote but white women did not in the wake of the Civil War. Franklin Roosevelt was an adulterer. Theodore Roosevelt was at times a warmonger. His views on American Indians are so dark at times that one hates even to read them in a scholarly arena. John F. Kennedy, LBJ, Ronald Reagan, Eisenhower, Bill Clinton, (where does this list end?) broke their marriage vows. Martin Luther King was a womanizer and he plagiarized his doctoral dissertation. Bill Clinton and George W. Bush evaded military service during the Vietnam War. Presidents Obama, Clinton, and GW Bush smoked dope. JFK dropped acid in the White House!

The only political figure I know who seems to have passed the righteous test in full purity is Jimmy Carter. That alone should give us pause. Where does this wave of righteous expurgation end?

4. 'Tis better to wrestle than erase. My mentor Ev Albers believed that the duty of the humanities scholar is to examine and explore, to try to put any text or historical act or individual in its context, to try to understand how things shook out as they did and not otherwise. The duty of the humanist is to explore the past for its complexity, richness, unresolvedness, nuance, paradox, and problematic nature, and not to engage in the lazy enterprise of making glib judgments. Judgement is easy, understanding difficult. It does no good to portray Jefferson as a lover of liberty who unfortunately was born into a world of slavery, but who treated his slaves well and tried to change the world of Virginia and the United States to the extent that he could; and equally it does no good to portray Jefferson as a contemptible hypocrite who talked the language of liberty and equality, but who was quite content to breed slaves for the marketplace, and who dismissed African-Americans as physically and mentally inferior. One could make either argument plausibly enough, for there is a huge and not always consistent body of evidence in Jefferson writings and actions.

But surely we gain more by wrestling with the paradoxes in Jefferson's life, illuminating, clarifying, teasing out nuance, attempting to understand his own (changing) thinking about race and slavery, his own strategy for preserving his reputation as an apostle of liberty while buying and selling human beings, who, as he freely acknowledged, "did him no injury." After spending thirty years thinking and writing about Jefferson, I am not at all sure I understand his relationship to race and slavery. I'm not done trying. But I refuse simply to condemn him before I fully understand him.

We cannot understand ourselves if we do not understand the unresolved and perhaps unresolvable complexities of our heritage. Jefferson's greatest biographers have said that the contradictions and unresolved principles in his life (1743-1826) are also the contradictions and unresolved issues in the American experiment. To understand ourselves, we must try to understand him. To judge him in a simplistic and self-satisfying way, means that we are short-circuiting our attempts to understand ourselves.

It would be insane, I think, to refuse to name an elementary school Martin Luther King, Jr., because he broke his marriage vows, or plagiarized his dissertation. It would be equally insane to remove Jefferson's statue from the campus of the University of Virginia or the University of Missouri or William & Mary. Much better to use the "offending" icons as a text to discuss, debate, wrestle with, maybe even throw eggs at on occasion. But to remove those statues because Jefferson has disappointed us, US!, is to lose an opportunity for a very serious conversation about the dynamics that produced the America of 2016.

The Culture of Outrage represents a very dreary path in our pursuit of happiness and justice. In my view, on the whole, all things considered, Thomas Jefferson (as well as Woodrow Wilson, though I'm not quite as sure about Cecil Rhodes) must be seen as a net benefactor of humankind. But I would not remove a statue of Jesse Helms, George Wallace, or for that matter Pitchfork Ben Tillman from its pedestal. Better to deliberate and debate, perhaps at the top of our lungs, than to erase that which we think we have transcended.

Further Reading:

- American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson by Joseph Ellis

- Thomas Jefferson: America's Paradoxical Patriot by Alf Mapp, Jr.

This week, please enjoy an extra addition here on the blog and in your podcast feeds: The opening chapters of Becoming Jefferson's People as read by Clay S. Jenkinson.

Clay S. Jenkinson discusses his book, Becoming Jefferson's People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century, in the second of two shows about the book.

Clay S. Jenkinson discusses his book, Becoming Jefferson's People: Re-Inventing the American Republic in the Twenty-First Century, in the first of two shows about the book.