As perhaps you know, I’m now the editor of the quarterly journal of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, We Proceeded On. That’s one of the refrains of William Clark’s journal of the 28-month expedition that was the brainchild of the great Jefferson. Whatever else was true, virtually every day (there were 1,123 of them), Clark announced that “we proceeded on”—from St. Louis to the shores of the Pacific Ocean.

Click to enlarge

The journal comes out four times per year. My fourth issue will appear in about a month. I’m so excited about it that I want to tell you what we have discovered, and I want to urge you to become members of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation and in so doing subscribe to the journal, which we Lewis and Clark obsessives call WPO, we proceeded on.

Lewis and Clark were explorers, which meant that they regarded themselves as the first white people to see whole swaths of the American West. Lewis, in particular, wanted to be first—first to see the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, first to view the Great Falls of the Missouri, which Lewis regarded as second only to Niagara Falls in sublimity, and maybe greater, first to bestride the source of what he called “the mighty and heretofore deemed endless Missouri River.” They were traveling through what Lewis called a landscape “2000 miles in width upon which the foot of civilized man has never trodden.” The word “discovery” is now pretty suspect. One person’s new discovery is another’s ancient homeland. Lewis and Clark were not traveling in a vacuum, no matter what they wanted us to believe. They depended on Native American informants, Native American guides (and I don’t mean Sacagawea), and Native American maps drawn with sticks and mud on the ground, or with charcoal on animal skins, and occasionally on paper.

Cartographers have identified at least ten places in the journals where the captains talk about the maps that their Indian hosts produced to help them figure out the lay of the land, and to know which tributaries and mountain ranges stood in their path to the Pacific.

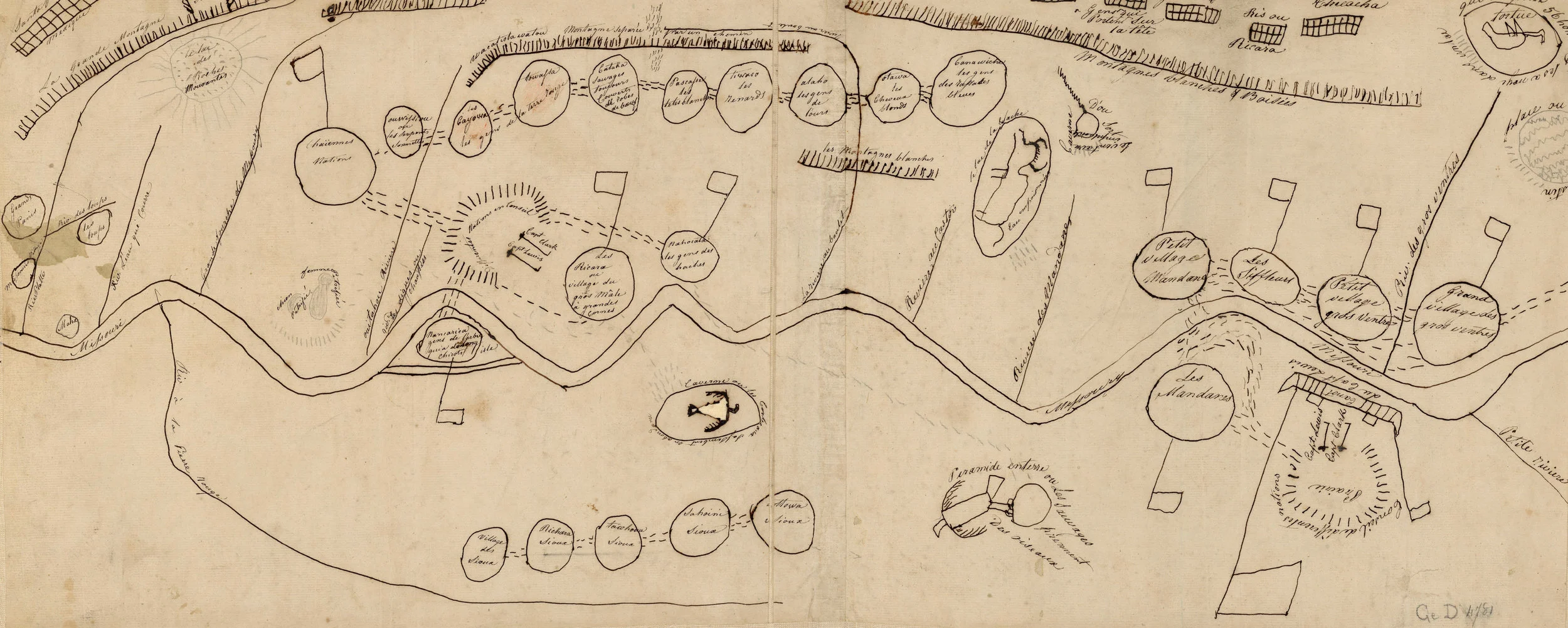

A couple of years ago a graduate student named Christopher Steinke, then at the University of New Mexico, discovered one of those maps. It was stored in the archives of the Bibliotheque nationale de France in Paris. Steinke was not a Lewis and Clark scholar. He was searching for North American indigenous maps at the Bibliotheque nationale when he stumbled upon one by an Arikara man named Piaheto or Arketarnarshar or Too Né. He wrote an article about it, with more emphasis on indigenous than on Lewis and Clark, in the outstanding William and Mary Quarterly.

As you know, every year I lead a cultural tour on the Lewis and Clark Trail in Montana and Idaho. We canoe through the White Cliffs section of the Missouri River east of Fort Benton, Montana, for three days, and then—after a hotel room and hot showers--we spend another three days hiking up on the Lolo Trail, the most pristine part of the entire national Lewis and Clark Trail. One of my favorite young guides, an archaeologist named Kevin O’Briant, told me at a place called Eagle Camp that he wanted me to see a map he had come across. We’re posting a photo of Kevin and me standing together with a copy of the map.

I was stunned. The map was made by Too Né, who traveled with the expedition for a few weeks in the autumn of 1804 in what’s now North Dakota. He went upriver with Lewis and Clark to try to make peace with the Mandan Indians, with whom the Arikara had been at war. He tried to inform Clark of some of the important landmarks, including sacred places, on that stretch of the Missouri River, between today’s North and South Dakota border and the earthlodge villages at the mouth of the Knife River in central North Dakota. In his journal Clark said he was indifferent to the geographic, historical, and sacred information Too Né was explaining to him through an interpreter. But the discovery of the map shows that Clark was listening more closely than he let on, and Too Né’s information did actually find its way into Clark’s journal.

All of this is spectacular news. It’s one of the most important discoveries in Lewis and Clark studies for a generation, since folks in Louisville, Kentucky, found a packet of 51 William Clark letters in an attic in the late 1980s. It may be more important, because it sheds important light on the expedition’s dependence on Native American maps; on the previously neglected role of Too Né as a Native American guide, interpreter, and diplomat; and on the significance of the expedition’s encounter with the Arikara in northern South Dakota.

When Kevin showed me the map, I immediately decided to dedicate a full issue of We Proceeded On to the Too Né map. I asked Kevin to write the lead article. He has written a wonderful essay about the ways in which Native American maps read the land differently from Euro-American Enlightenment maps. We’re publishing the map in a pull-out centerfold. I call it Lewis and Clark porn. I asked the two leading Lewis and Clark cartographers, both eminent individuals, Herman Viola and John Logan Allen to assess the map. Before fulfilling my request, they made me send them wonderful huge laminated copies of the map. Their assessments are amazingly generous and insightful. I interviewed Chris Steinke, the discoverer of the map. I found Jefferson’s letter of condolence to the Arikara—Too Né visited the Great Redheaded Father in Washington, DC, and unfortunately died there on April 6, 1806. And I found a multi-page description of Too Né in the nation’s capital by a painter, man of letters, playwright, and actor William Dunlap. And I wrote an essay about the ways Too Né’s map tracks with Clark’s journal from October 8 to November 10, 1804.

This will be one of the most important issues of We Proceeded On in a very long time, perhaps forever. I even got an artist friend of mine, Katrina Case-Soper to paint a courtroom-like watercolor of Too Né in the Washington boarding house where he stayed in the weeks before his death.

You can sense how excited I am about this, and how proud I am to serve as editor for this critically important moment in the long history of Lewis and Clark studies. I hope you will subscribe to WPO starting immediately. Just go to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage website. Their headquarters is in Great Falls, Montana. You will find more information about all of this on our website.

A couple of weeks ago I made a pilgrimage to one of the sacred places on Too Né’s map. It’s called Medicine Rock, located near the Cannonball River in southwestern North Dakota. It’s a lonely outcropping in the middle of the middle of nowhere. Virtually no non-Indian North Dakotans know that Medicine Rock exists. It was a windy, cold, gray, winter day on the northern Great Plains, with ground blizzarding on the narrow two lane roads, followed by gravel roads, followed by a two-trail path in the middle of an immense grassland. I had to walk a mile into a stiff wind, windchill about ten below zero, to get to the sacred place. And there, in this non-descript bit of sandstone in the infinite expanse of the Great Plains, where a protective chain link fence surrounds the perimeter of the Medicine Rock site, I found prayer bundles—thumbsized plugs of tobacco wrapped in bright cotton handkerchiefs—tied to the fence.

Think about this. It’s the second decade of the twenty first century, and I got to the site partly by using the Google earth app on my smartphone. We need these reminders that there are still sacred places all around us, and that the white history of America, particularly the Great Plains, is very recent.

Robert Frost was right. “The land was ours before we were the land’s.”

Clay Jenkinson welcomes back David Nicandri for a discussion about Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton, the explorer who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic. They also talk about Thomas Jefferson's influence on exploration. Nicandri is the author of River of Promise: Lewis and Clark on the Columbia and Captain Cook Rediscovered: Voyaging to the Icy Latitudes.