Jefferson famously wrote, "No man will ever carry out of the Presidency the reputation which carried him into it."

Think of the diminishment of the presidents even of my own lifetime. Lyndon Johnson had been so consumed by the War in Vietnam that he withdrew from the 1968 presidential race. Johnson loved and lusted for power as much as anyone who has ever been President of the United States. But by the time he made his announcement, at the end of March 1968, he no longer dared to leave the White House because of the protests that followed him everywhere he went. Imagine hearing the chants: “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” He was a broken man—his whole dream of his life shattered—by the time he limped away in January 1969, after watching a man he regarded as a thug and a travesty of American values, Richard Nixon, inaugurated in his place. LBJ died quietly in 1973, far away from the arena, a haunted and fragile remnant of his larger-than-life persona.

Richard Nixon became so embroiled in the criminal presidency that we summarize under the term “Watergate,” that by the last weeks of his uncompleted second term he actually told the people around him that he wanted to die, that he had gone to sleep the night before hoping that he would never wake up. Whatever you think of Richard Nixon, one of the most intelligent, thoughtful, geopolitically savvy individuals ever to serve as President, it’s hard to know this—the depth of his unalloyed misery in August 1974—without feeling some compassion for the man. Richard Nixon: the president who wanted to die rather than face the humiliation of resignation.

Jimmy Carter came into the presidency in 1977 with his goofy smile, his cornpone innocence and virtue, his folksy small town values, his vow never to lie to the American people, his promise to heal the nation. Carter wound up being a failed one-term president, partly because he was micromanager, even controlling the calendar for the White House tennis court; partly because he dared to tell the American people the truth, that something was deteriorating in the American spirit, and partly because of the impotence of being president when the Islamic terrorists decided to humiliate America for 444 straight days during the Iran-hostage crisis, which among other things birthed the late night cable television talk show.

If you look at the before and after photographs of American presidents—all that vitality, including dark hair, health, and optimism—when they take the oath of office, and then the grayed-out, sunken-eyed, exit photos of mostly good men whose lives have been damaged by their time as president, whose lives have literally been shortened by the presidency, you wonder why anyone would want to reach that pinnacle of American life. When he was elected vice president in 1796, Jefferson said, in relief, "The second office of this government is honorable and easy, the first is but a splendid misery."

As I speak these words, former president George Herbert Walker Bush hovers near death. He cannot live much longer. Like many deeply devoted spouses, he loosened his grip on life when his beloved wife Barbara died in April 2018. Mr. Bush may have been fortunate to have been retired from the presidency after a single term. It is possible that it lengthened his life. At just under 94, he is already the longest living former president, edging ahead, for what it is worth, of Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan, both of whom lived to 93. Jimmy Carter is also 93, will be 94 in October, and it seems likely he will outlast them all. Carter has already written 37 books, which means that if he lives a few more years he will top the writingest president Theodore Roosevelt, who wrote 40 books depending on how you count.

Bill Clinton was one of the smartest, best-read, overtly brilliant individuals ever to become President of the United States—remember when he could instantly name and characterize the heads of virtually every country, including piddling ones, of the world?—but he gave his place in history to his penis. I remember seeing him on C-SPAN, sitting glumly while someone else spoke, when the controversy was at its height. He looked so profoundly self-disappointed—that all he had wanted all of his life was to be president, had lived for nothing else, really, and then he had squandered it all for a series of pathetic dalliances with interns—that I’m sure there were moments when even Bill Clinton wished he were dead. He got through it and the American people stuck with him—a booming tech economy did not hurt—and wound up being one of the better former presidents, although the word peculation will haunt him through history almost as much as priapism.

Ronald Reagan is every conservative’s favorite President. Many would erase someone from Mt. Rushmore and replace it with Reagan’s chiseled Hollywooden visage there, but he governed far closer to the middle than his admirers like to admit, and by the time his second term was well underway he was beginning to suffer from encroaching Alzheimer’s disease, a bit like one of those Soviet premiers of the 1970s and 80s who used to be propped up for photo ops. The Iran-Contra Scandal was worse in many respects than Watergate and for it President Reagan probably should have been impeached—waging secret wars against the explicit forbidding of Congress—are we a republic or a monarchy?—but the country didn’t have the heart to do it and so Reagan, who was really just a tired old befuddled man by the time he flew away to California, was permitted to serve out his second term. He was, probably, too old to be president. His mental deterioration is very sad. He and Nancy Reagan handled it with candor and dignity, but we need to remember that the White House is not a senior care facility. We need our presidents to be alert, fully functioning, and on top of the profound responsibilities of the job.

George W. Bush was a kind of smart aleck going in, all that shucking and shrugging and smirking, but 9-11 and his wars in Iraq and Afghanistan transformed him visibly, matured him, humbled him, deepened him. He has been a truly discrete and dignified former president, and his willingness to express his soul through painting, even though he is not even as talented, say, as Winston Churchill, is wholly admirable, I believe.

And then, of course, there is Donald Trump. I will only make the following predictions. I do not believe he will serve out his term. He promised to drain the swamp, but his presidency—his sons, his son-in-law, his cronies, his violations of the emoluments clause of the Constitution, his personal attorney, his grifting cabinet officers, particularly Scott Pruitt—have turned the executive branch into a kleptocracy. If 40% of the American people can still believe that he is a welcome breath of fresh air, then it’s on us, not him. The old adage that in our democracy we get what we deserve sounds pretty ominous right now. But it seems so true, alas.

Finally, a word or two about Thomas Jefferson. His first term was mostly splendid—culminating in the Louisiana Purchase and the authorization of the Lewis and Clark Expedition—but in his second term America was nearly crushed between the two great European powers, France and Britain, locked in an existential world struggle for survival, and nothing that Jefferson could do, nothing he could imagine, could protect America from a series of national humiliations. The embargo acts failed to accomplish what Jefferson and Madison had in mind for them—that economic coercion would bring Britain and France to their senses—and meanwhile those coercive acts offended the farmers and merchants of the United States to the point of open rebellion. Jefferson, who came into the presidency at the age of 57 wondering if he were too old for the responsibilities and challenges ahead, felt physically, intellectually, and spiritually exhausted by the time he left office in March 1809. In fact, he had essentially abdicated the presidency in the last half year of his second term, making his handpicked successor Madison the de facto president of the United States, months before his inauguration.

Fortunately, Jefferson found healing and renewal at his beloved Monticello—particularly in the presence of his fabulous, beloved daughter Martha, and he lived seventeen more years. And talk about great former presidents, Jefferson still had in him—exhaustion notwithstanding—one more magnificent achievement, mightier perhaps than any other person who has ever been president of the United States, by which I mean: the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.

Nobody else can match that. Period.

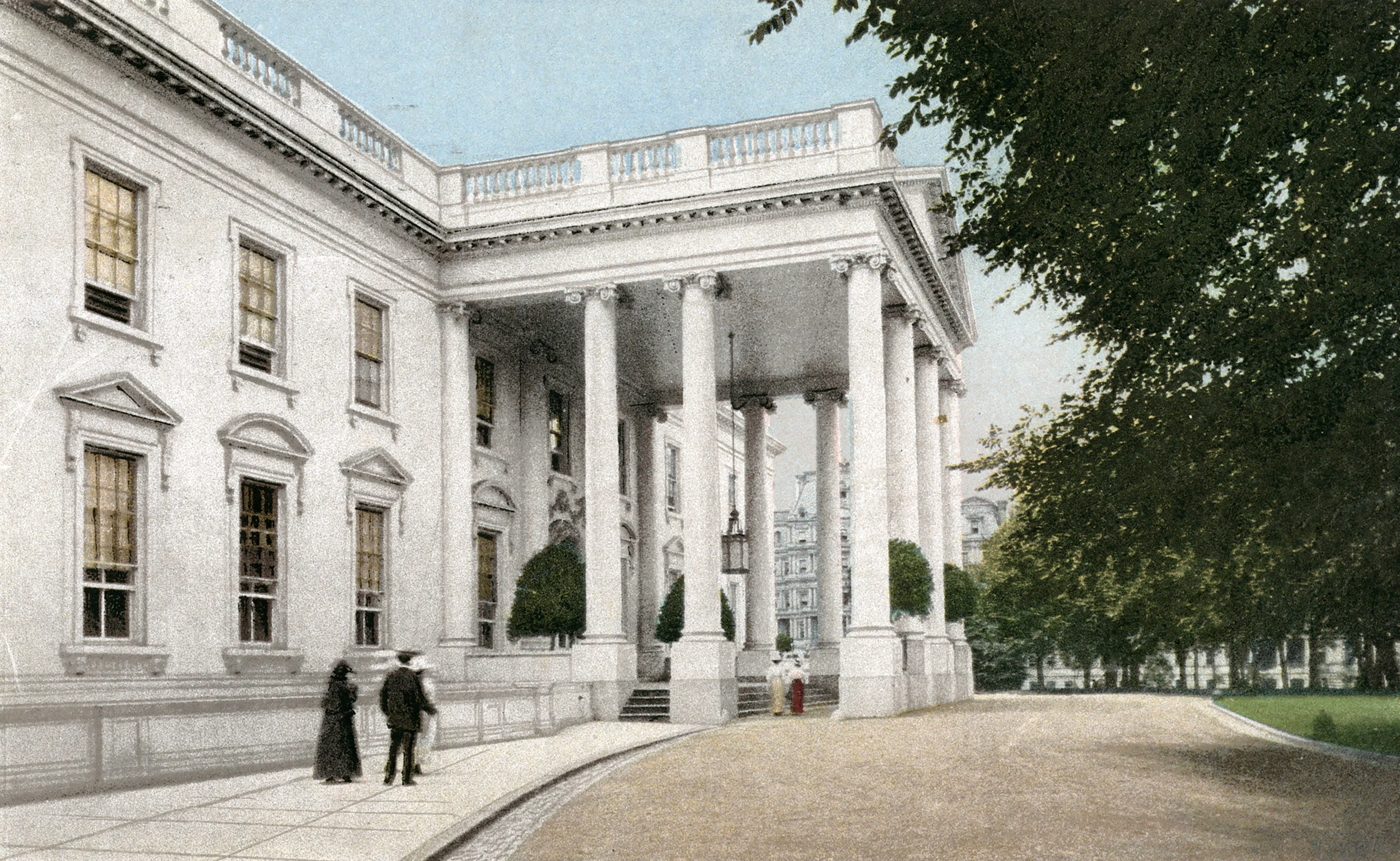

White House Entrance from the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

This week, Clay Jenkinson discusses Jefferson’s first inaugural address with regular guest Lindsay Chervinsky. The speech, inaudibly delivered on March 4, 1801, is regarded as one of the top five in American history.