North Dakota is bisected by a great river, which flows into one of the world's great rivers, the mighty Mississippi. The Lewis and Clark story (1804-06) produced the greatest book ever written about the Missouri River, but to this date there has never been a great Missouri River novel. The Mississippi has inspired a rich alluvium of literature, including some of T.S. Eliot's most beautiful lines of poetry. But surely the two greatest pieces of Mississippi River literature were written by the same man, Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). Twain's nonfiction essay and memoir, Life on the Mississippi, was published in 1883. Two years later he released a classic of world literature and arguably the Great American Novel, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Having given up television for Lent, and wanting to give myself the best possible 60th birthday gift, I decided to reread Huckleberry Finn. I don't know how many times I have read it over the course of my life—somewhere between five and ten—but I had not read it in years. I bought a lovely new "special edition" copy of the novel, selected a perfect light red reading wine, and sat down in my favorite reading chair with my new sexagenarian progressive-lens glasses (goggles).

"Mark Twain, Stormfield, December 21st, 1908." 1913. From the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

There is almost nothing I love more than settling in with time on my hands for a leisurely read of a book that deserves our best attention. I read for a living, more or less, and I wind up clawing my way through a good deal of prose that is not particularly pleasurable or well-written. Often enough, I'm hurrying through a stack of books because a deadline is looming over my head like an executioner's sword. I get very few opportunities for free reading in an average week and, when I do, I usually turn to Charles Dickens.

If you haven't read Huck Finn, or haven't read it for a while, I strongly urge you to give yourself that pleasure soon. I knew it was a great novel, but I had forgotten how wonderfully funny it is. There I was in my living room, all alone in a darkened space with only my favorite reading lamp casting an aura of light about my head and neck, shelves of books rising up to the ceiling in every direction, and only the quiet whir of the furnace to cut the silence of the evening, laughing out loud every couple of pages. At times I had to get right up out of my chair I was so perfectly delighted by some moment in the text, as when Huck says of a funeral director, "There warn't no more smile to him than there is to a ham."

The great Christian apologist and literary critic C.S. Lewis said of Spenser's Faerie Queen, "To read it is to grow in mental health." To read Huck Finn is to grow in mental health, even though the book is a savage satire on "shore life" in America in the mid-19th century. Huckleberry Finn is the story of a runaway slave, Jim, and a runaway boy, Huck, one black, one white, one married with children, the other a child of 12 or 13 whose mother is dead and whose father is a violent drunkard and wastrel. They fall in together and determine to flee from their troubles by floating down the Mississippi River on a raft to the mouth of the Ohio at Cairo (kay-ro), Illinois, where Jim will be able to enter the free states of the Northwest Territory, and Huck will be away forever from the beatings and psychological torture of his father "Pap."

When they are alone on the raft drifting down the Mississippi, Jim and Huck enter a kind of timeless paradise, an American Eden in which they are both for the first time free in the fullest sense of the term, and where life is reduced to its most basic rhythms and loveliness. Some of the greatest passages Twain ever wrote, some of the greatest passages in American literature, explore the romance of a river voyage where the river does all the work, and the voyageurs just laze about fishing and talking. (Read chapters 16 and 1 if you want to get the full flavor).

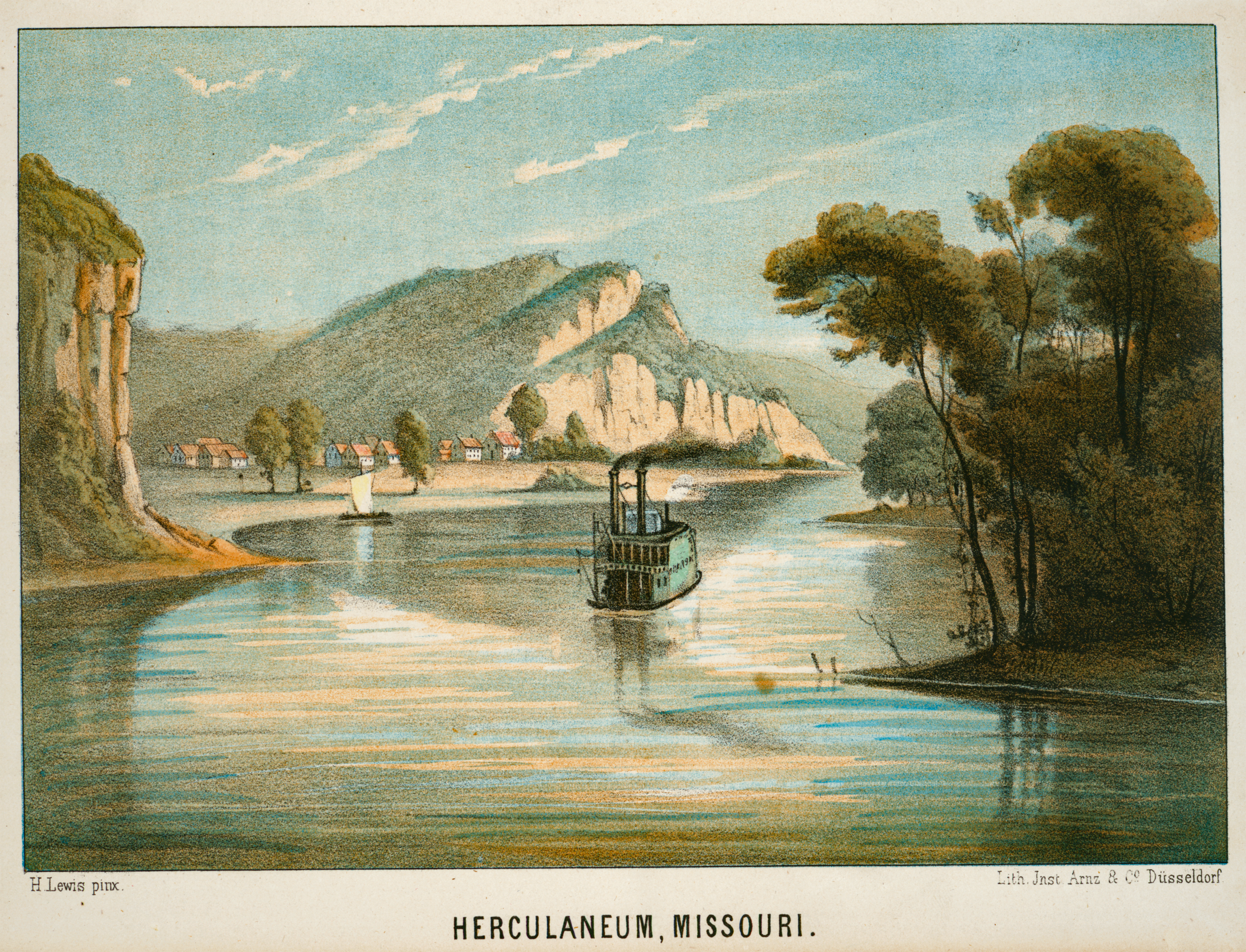

"Herculaneum, Missouri." 1854 - 1857. From the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

"We slid into the river and had a swim," Huck says, "so as to freshen up and cool off; then we set down on the sandy bottom where the water was about knee deep, and watched the daylight come. Not a sound anywheres—perfectly still, just like the whole world was asleep, only sometimes the bullfrogs a cluttering, maybe." This is exquisite, made more so by the slang "anywheres." As they lie on their backs on the raft gazing up at the stars, Jim and Huck have a lyrical debate about whether "they was made or just happened." They listen to sounds far off—voices from all the way across the mile-wide river that make them feel all over "crawly." Huck: "We said there warn't no home like a raft, after all. Other places do seem so cramped up and smothery, but a raft don't."

Huckleberry Finn was controversial when it was published in 1885, and it has been controversial in a range of ways ever since. At first it was considered coarse and vulgar, and one moral authority denounced it because Twain permitted Huck not only to itch, but (horrors) to scratch in the course of the story. For the last thirty years or so, the issue has been the n-word, which Twain uses more than 200 times in the novel. Hundreds of K-12 school systems no longer teach the novel because of the ubiquity of the n-word. I disagree with that decision—Huck Finn is not only a great book, but a very important book—but I can understand why school administrators, teachers, and parents are squeamish about it.

My father used to say, "Great literature is its own apology." If you want to understand the moral complexities of slavery in American history, and the struggle in all cultures between human law and "higher law," there is no better start than Huckleberry Finn. Twain set out to write another entertaining "boy's book" like his popular Tom Sawyer (1876), got stuck and put the manuscript aside for several years, then returned to complete a work of literature of the greatest profundity. That makes for some unevenness in the style and tone of the novel.

Huck's slow realization that Jim is a dignified human being and a true friend in addition to being a Negro slave redeems, in my view, whatever is goofy or "offensive" in Huckleberry Finn. There are moments in Huck Finn that make you glad to be an American, and plenty of moments that make you wrestle with the dark side of American life: hypocrisy, racism, demagoguery, fraud, sanctimonious righteousness, violence, and what Huck calls "humbug." Life on the raft is idyllic. Life on either shore is full of lynchings, cold blooded murders, feuds that never end, domestic violence, alcoholism, torture of animals, and the original sin of slavery.

And yet, for all of that, Huckleberry Finn is an amazingly joyous book. You will laugh out loud.

I know a little about drifting down a great river with no agenda but lazing through the summer's day, but I have never felt the terrific tug of the Mississippi River drawing everything it touches inexorably towards the Gulf. I want that experience, and not in a faux steamboat or the Delta Queen.

This week, an interview with Clay S. Jenkinson about his new book, The Language of Cottonwoods.

We're joined by Char Miller to discuss a new book, Theodore Roosevelt, Naturalist in the Arena. The book is a collection of noted essays by Roosevelt scholars and was edited by Miller and Clay Jenkinson. Char Miller is W. M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History at Pomona College.

"Understand him for his flaws as well as for his greatness."

— Joe Ellis

We welcome historian Joseph Ellis to the program this week to talk about his book American Creation. In the book, Ellis notes a series of five contributions the founding fathers made and Clay Jenkinson asks how those contributions are holding up during our time.

Over the past few days I have had the wonderful guilty pleasure of sitting down to read Robinson Crusoe cover to cover. I know I should have been doing other things, some of them pressing, but I just sat there and read this famous and fabulous account of a man who is shipwrecked on a small island off of Venezuela and spends 28 years there, 26 alone with a parrot and some semi-domesticated flocks of goats.